Contexts

Explore these objects’ changing social contexts

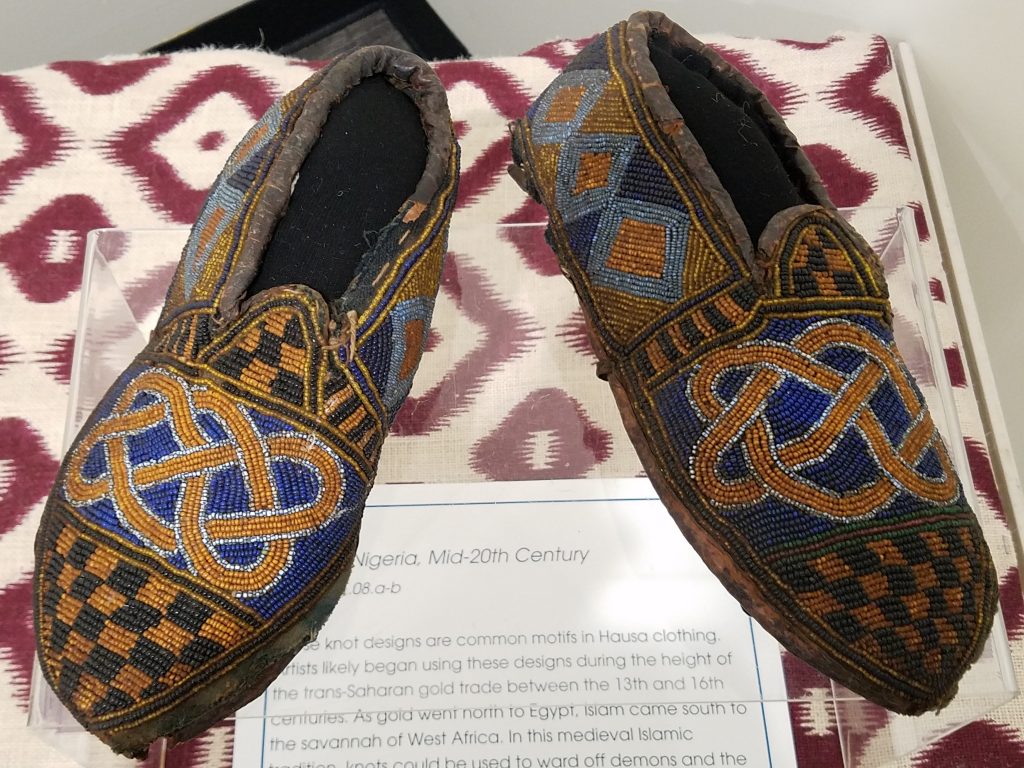

Shoes

Hausa, Nigeria, Mid-20th Century

2018.07.E.08.a-b, from the Stanley P. Bohrer Collection

Loose knot designs are common motifs in Hausa clothing. Artists likely began using these designs during the height of the trans-Saharan gold trade between the 13th and 16th centuries. As gold went north to Egypt, Islam came south to the savannah of West Africa. In this medieval Islamic tradition, knots could be used to ward off demons and the Evil Eye. A specific kind of knot, dagin arewa, is still used today to symbolize the Hausa culture.

Curated by Dr. Andrew Gurstelle (MOA).

Necklace

Navajo, United States, Mid-20th Century

2018.04.E.01, Gift of Mr. Frank Warfield

Southwestern Native American jewelry originated in the 19th century with Spanish missionaries, but its social context has often been misunderstood. In the 1950s, travel and fashion magazines promoted Native American jewelry—and increased its market value, too. This helped jewelers preserve their art as part of larger efforts to preserve Native American cultures. This concho-style necklace features Catholic crosses inside of flowers are etched into each disc.

Curated by Andy Chen (’22).

Textile

Swahili, Tanzania, Early 21st Century

2019.08.E.01, Gift of Vera Kamm

Since the late 18th century, khanga cloths have become an important medium of communication in East Africa. The Swahili text on the clothing can be more important than its design, color, or quality. Today, modern khanga designs often have a riddle or proverb written on them, known as jina. For example, this khanga cloth contains the phrase: “Mkono Wa Mungu Hakuna Wa Kuushinda”, which translates to “the hand of God is not to be overcome.”

Curated by Emily Wilmink (’20).

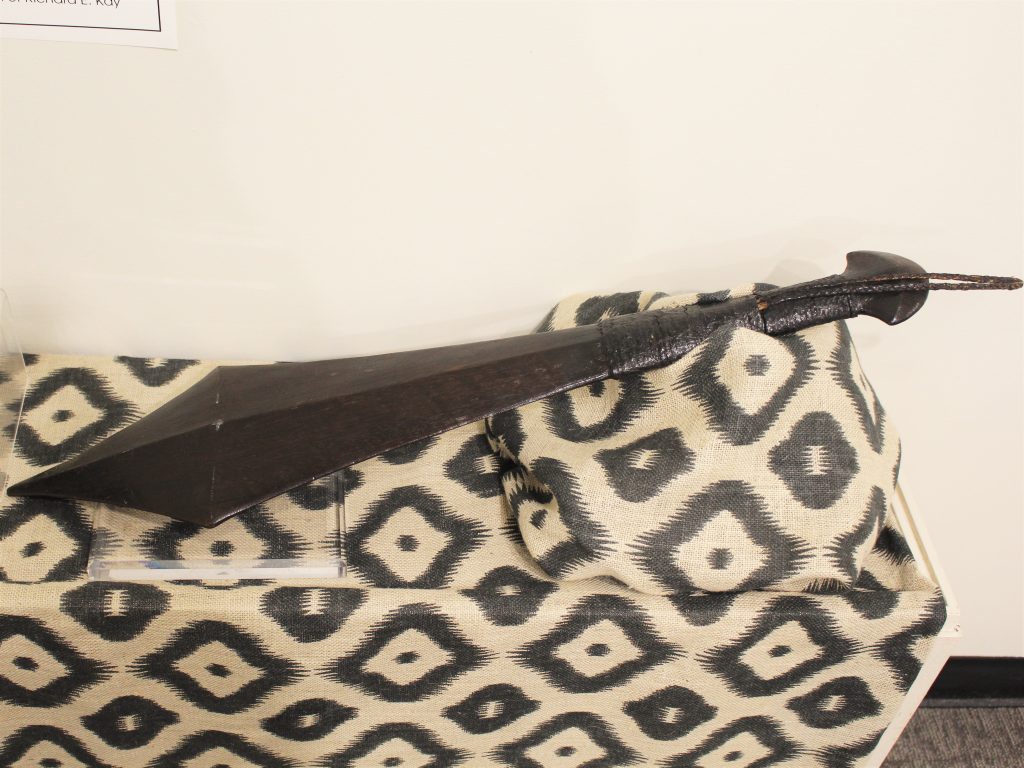

Club

Melanesian, Solomon Islands, Mid-20th Century

2019.10.E.11, Gift of Laura Guyer

Subi clubs, said to originate on the island of Malaita, are identified by their diamond shape. The recorded history of this particular club claims it was used on the island of Guadalcanal during World War II by a person identified as Chief Steven of Lambi. Beyond the general cultural significance of subi clubs, this specific club also represents a time of colonialism and military occupation.

Curated by Lillian Remler (’22).

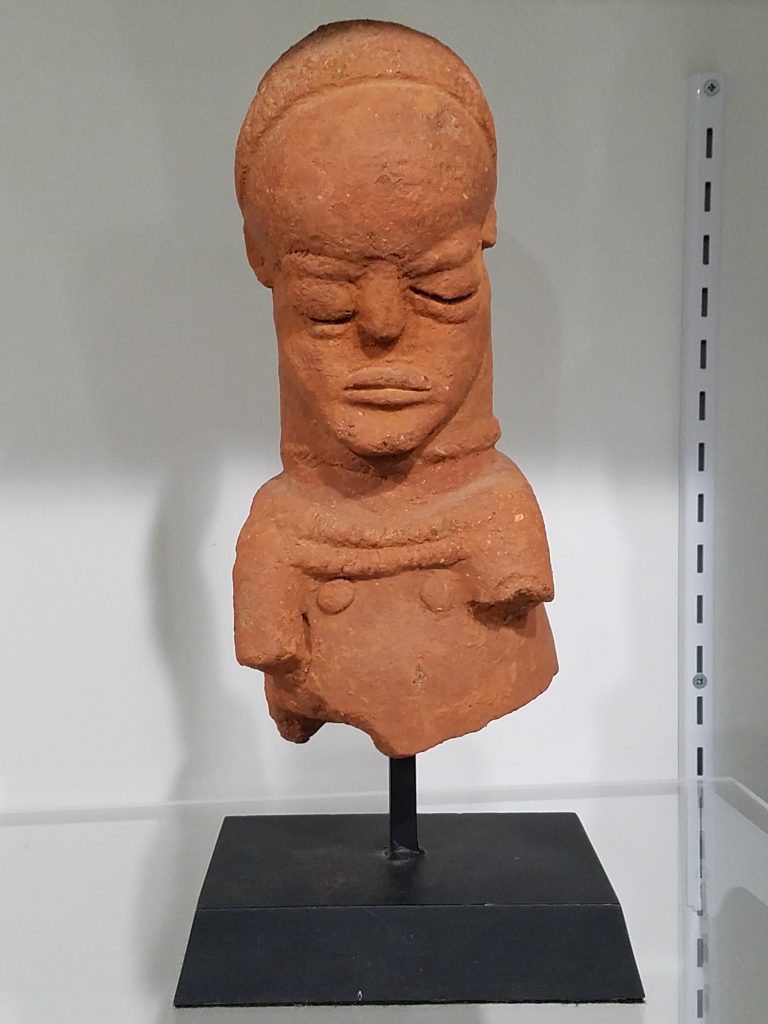

Sculpture

Katsina, Nigeria, 200 BCE to 100 CE

2019.07.A.20.a-b, Gift of David & Karina Rilling

The Katsina culture is a historical and anthropological mystery to scholars, as it was not recorded until 1928 when figurines like this were accidentally discovered during tin mining near Nok village. However, no controlled archaeological projects were carried out at the Katsina site. It is likely this figurine was recovered illegally, thus little research about it exists. However, some research on the Katsina culture suggests it dates to the early iron age.

Curated by Meredith Groce (’21).

Doll

Japanese, Japan, Late 20th Century

2018.11.E.04, Gift of Stefan Chiarantano

Traditional kokeshi dolls were made by woodcutters beginning around 200 years ago. It became too cold to work in the forests during the winter months, so they made simple, cylindrical dolls out of scraps of wood to sell as children’s toys. Around 1900 CE, the dolls started to appeal to adults who sought them out as collector’s items. Modern kokeshi dolls can take on the appearance of pop culture characters.

Curated by Robby Outland (’21).

Baby Carrier

Unidentified Culture, China, Late 20th Century

2018.12.E.01

The “back belt” baby carrier is an important daily necessity for women in southwestern China. There are more than 30 minority cultures in this region. Each culture uses different patterns and decorations, though it is hard to identify which culture this baby carrier belongs to. Baby carriers are hand-made in a meticulous process including weaving and embroidery. These skills have a long history among the folk traditions of China.

Curated by Ziyi Qin (’22).

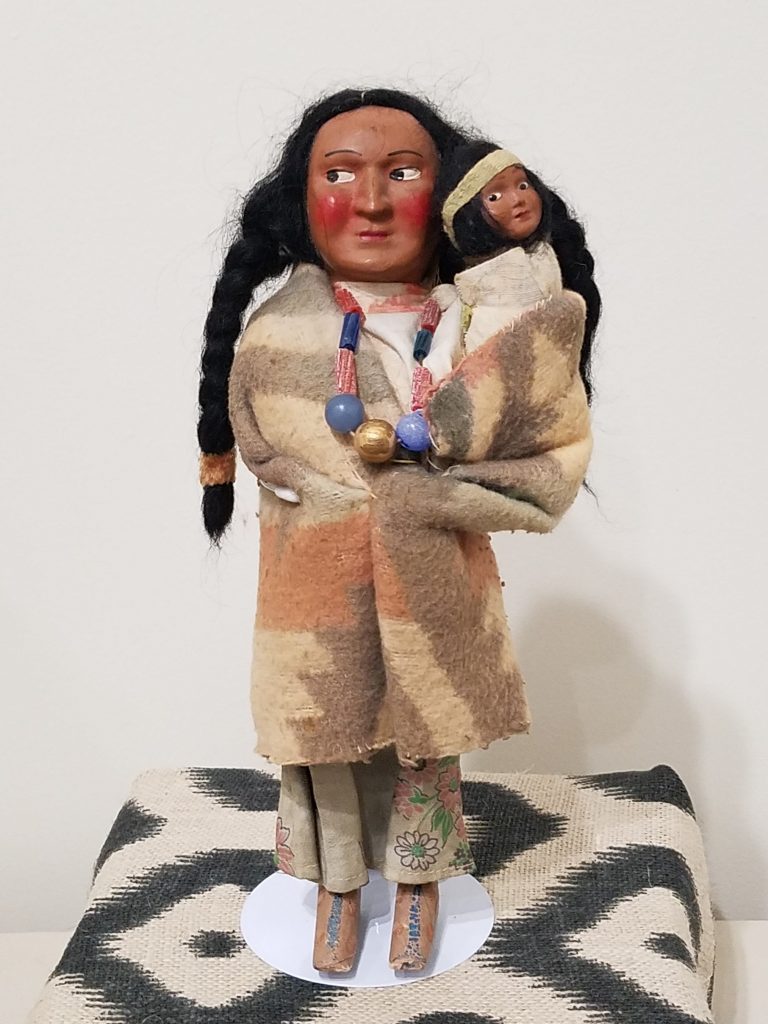

Doll

American, United States, Early 20th Century

2019.06.E.08, Gift of Lois Markham

Skookum dolls were first made by Mary McAboy in Missoula, Montana, in the 1910s. The name comes from a Chinook and Siwash expression used in the Pacific Northwest to mean very good, excellent, or large. Skookum dolls were styled to depict Native American people and the different tribes to which they belonged. They were mainly created for tourists and schoolteachers to represent Native peoples, even though they were not authentic cultural objects.

Curated by Rachel Lampman (’22).

Explore the other sections of this exhibit below