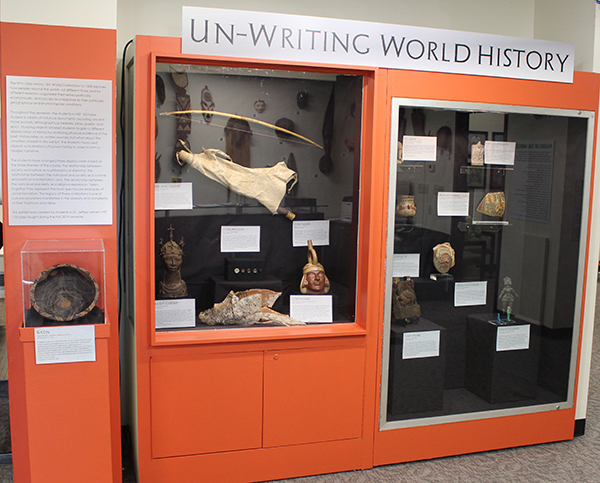

Un-Writing World History

The Wake Forest class History 103: World Civilizations to 1500 explores how people around the world—at different times and for different reasons—organized themselves politically, economically, and socially as a response to their particular geographical and environmental conditions.

Throughout the semester, the students in HST 103 have studied a variety of historical documents, including ancient travel journals, ethnographical treatises, plays, poetry, and epics. Studying objects allowed students to gain a different appreciation of history by showing physical evidence of the past. History relies on written sources, but what about the unwritten stories? In this exhibit, the students have used objects as illustrations of human history in order to form a deeper narrative.

The students arranged three display cases based on the three themes of the course: the relationship between society and nature as a philosophical dilemma; the relationship between the individual and society as a cultural and political manifestation; and, the relationship between the individual and deity as a religious expression. Taken together they represent the most spectacular examples of social formation. The legacy of these civilizations is one of cultural syncretism manifested in the diversity and complexity of their traditions and ideas.

This exhibit was curated by students in Dr. Jeffrey Lerner’s HST 103 class taught during the Fall 2019 semester.

Society & Nature

Basin

3200-2700 BCE | Neolithic Majiayao (China)

2012.01.A.134

A skilled craftsman made this basin to store items food at a time when society was beginning to move away from hunting and gathering and towards agriculture. Agriculture and domesticating animals allowed people to have more free time leading to specialized labor, which in turn led to specialized technologies. Their success as farmers allowed them to create a surplus of food, which led to the demand for containers like this basin to store grain.

Curated by Katharine Hsiao

Individual & Society

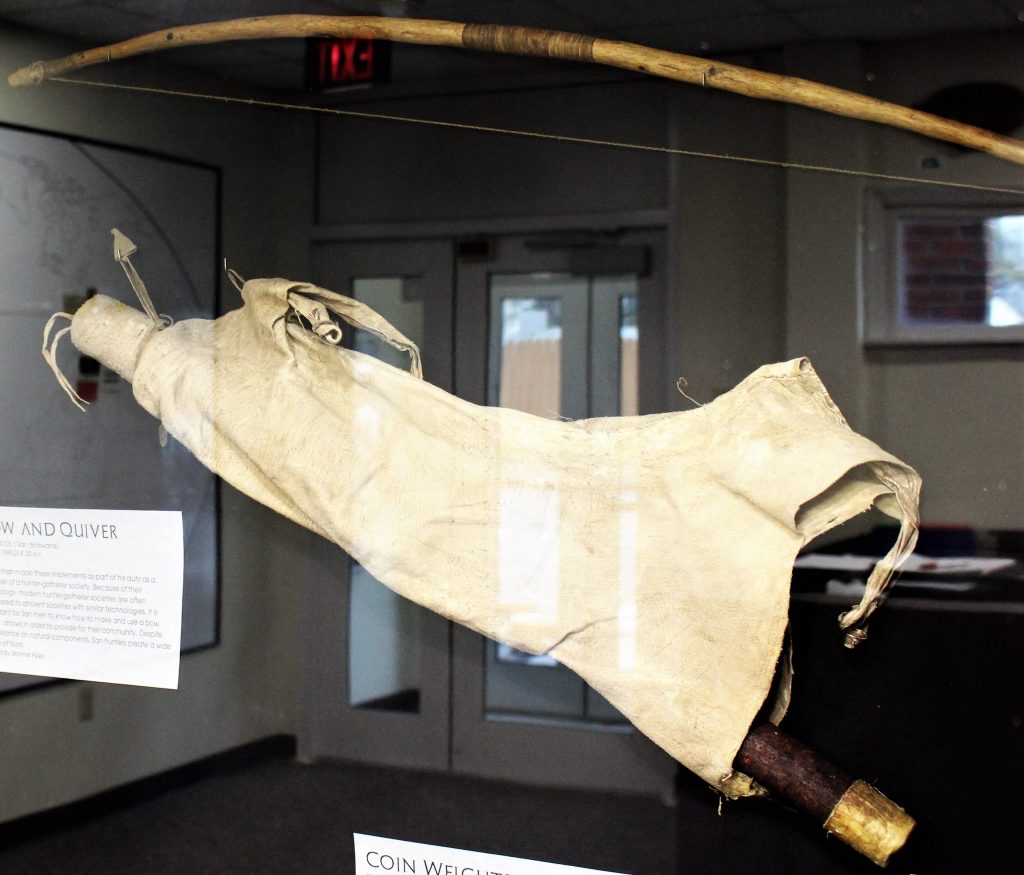

Bow and Quiver

ca. 1970 CE | San (Botswana)

1990.01.E.20.a-c

A San man made these implements as part of his duty as a member of a hunter-gatherer society. Because of their technology, modern hunter-gatherer societies are often compared to ancient societies with similar technologies. It is important for San men to know how to make and use a bow, quiver, arrows in order to provide for their community. Despite their reliance on natural components, San hunters create a wide variety of tools.

Curated by Brionne Pyles

Head Figurine

ca. 1970 CE | Edo (Nigeria)

2016.01.E.01

The brass head figurine of King Oba Akenzua II offers us insight into the relationship between the king and his people. To the people of Benin, brass was selectively used for head figurines of the Oba, or “ruler.” This head is a post-colonial revival of an ancient practice honoring patriarchs. Noblemen below the Oba within the social hierarchy had wooden heads carved in their honor, while commoners below them made terracotta heads in honor of their kin.

Curated by Clay Swiecichowski

Container

27 BCE-180 CE| Roman Empire (Adriatic Sea)

1992.01.A.1 a-c

Roman merchants used amphorae for shipping liquids, like wine or olive oil. Charting the locations of amphorae shows how merchants used containers like these to sell their goods throughout the Mediterranean. This vessel indicates the global commerce that underpinned the economy of the Roman Empire. Archaeologists recovered the three fragments of this amphora from a shipwreck in the Adriatic Sea. When recovered the vessel was covered in barnacles.

Curated by Diego Ventosa

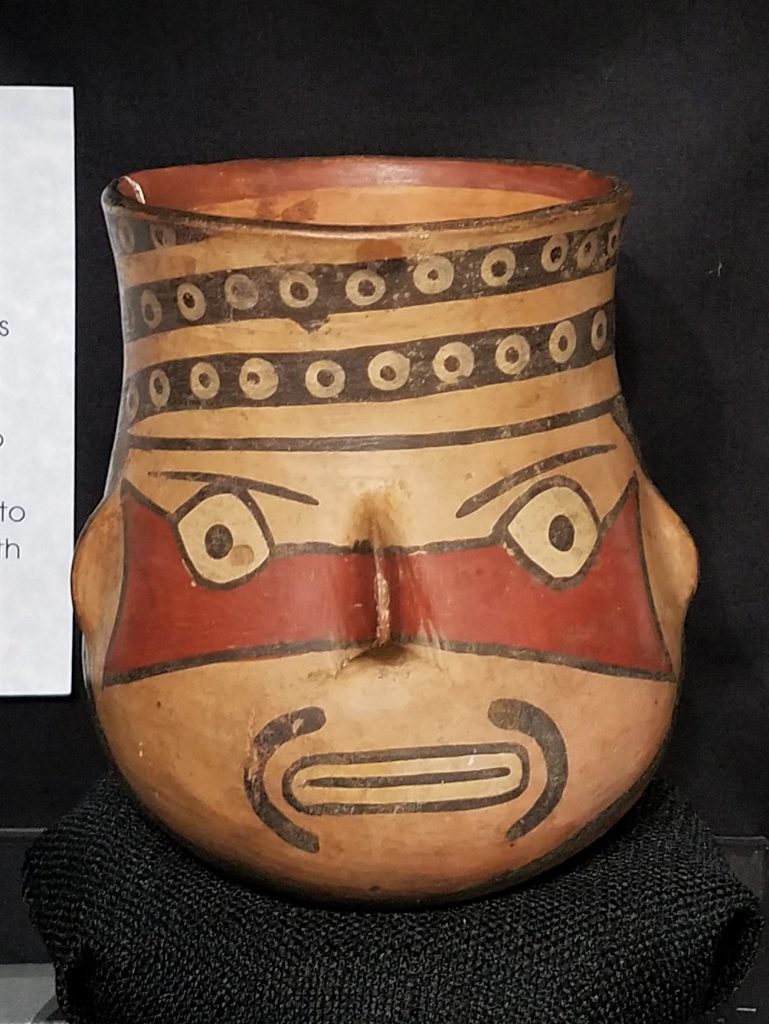

Container

200-800 CE | Moche (Peru)

1989.03.A.045

This mold-made artifact was crafted from the clay of the northern deserts of ancient Peru. It is one of many portrait head vessels designed by the Moche. Liquids, most often water, were stored inside the head and poured out through the opening during ritual ceremonies. The male figure depicted on the vessel may have been of high rank and wanted to be remembered, so he had his portrait made. This individual might have been a warrior or priest.

Curated by Ethan Harrison

Coin Weights

967-1171 AD | Fatimid (Egypt)

MOA# 2005.08.A.1-5

The most common use of Fatimid glass jettons, or disks, was as coin weights – to determine the value of coins. In the Fatimid Empire, there were no copper or bronze coins, because only gold and silver were used as currency. It is possible that these glass jettons circulated as unofficial token money among the common people to purchase inexpensive items, since it was impractical to do so with silver or gold coins. These objects were probably never accepted as official currency.

Curated by Dillon Ebner

Individual & Deity

Figurine

ca. 600 CE | Classic Veracruz (Mexico)

1989.03.A.062

This figure commemorates the elite residents of ancient Veracruz. The figure is ceramic and has a ‘palma’ ornament on its head. Elites served as religious officials and often participated in the Mesoamerican ball game. The ball game was not a simple sport but rather a solemn ritual. Sacrifice and other ceremonial rites were organized around the ball game.

Curated by Eli Yankelevich

Container

ca. 300 CE | Nazca (Peru)

1989.03.A.049

An artist in the Nazca civilization created this object to serve as decoration or to use in a religious ritual. The container was formed using slip, which allowed the Nazca to encompass a broader array of colors. The two rows of staring eyes at the top might represent a hallucinogenic state. This relates to the broader practice that many shamans would often take drugs to experience visions of supernatural spirits and communicate with the gods.

Curated by Shrey Parikh

Fertility Statuette

ca. 200 BCE | Ptolemaic (Egypt)

2017.07.E.05.a

This statue depicts the goddess Isis-Renenutet, an amalgamation of two different deities. Representing fertility of the harvest and motherhood, this statue would have been popular with agricultural laborers. The cult of Isis was found throughout the Mediterranean, from Egypt to Rome and Greece. Notice the item depicted to the right of the goddess; other identical artifacts from Egypt call this item the “Torch of Demeter,” referring to the Greek goddess of the harvest.

Curated by Eric Ross

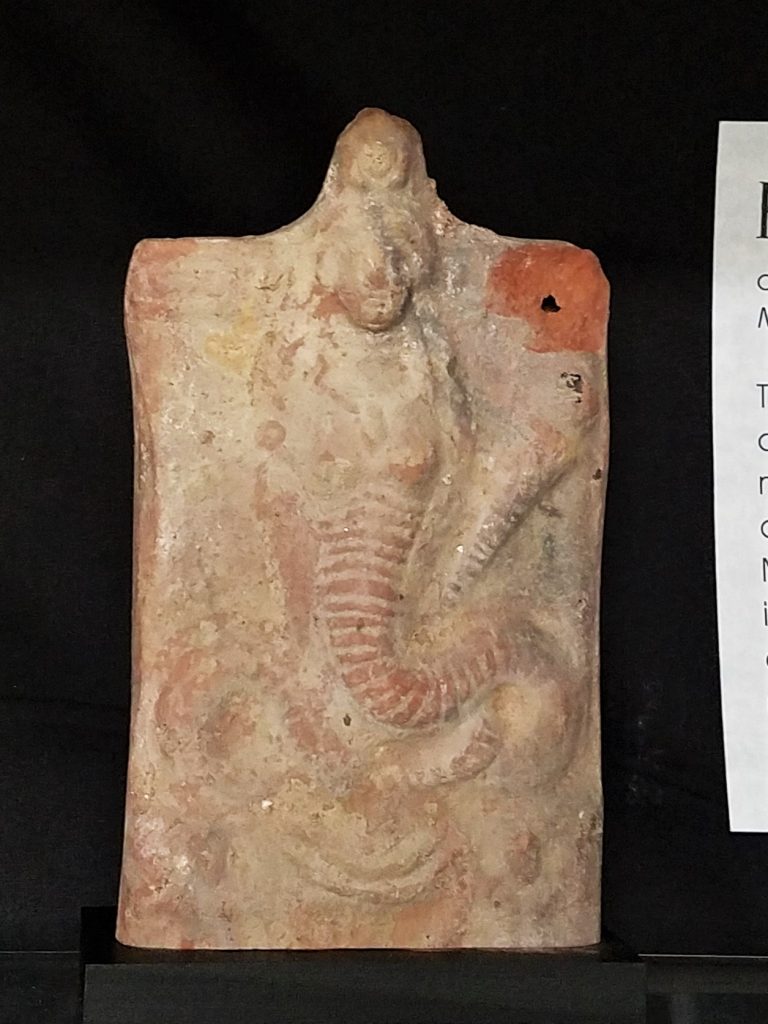

Fertility Figurine

400-200 BCE | Mauryan (India)

2017.07.E.36

This fertility figurine perhaps represents a Mother Goddess. There is debate among archeologists as to what purpose figurines like this one served. Some argue that these artifacts were worshiped as goddesses, while others maintain that they were offerings to the gods. The figurine is made of ceramic. Ceramics became a popular medium when Mathuran society became more urbanized. As a result, these kinds of figurines also become more stylized and detailed.

Curated by Walter Jackson

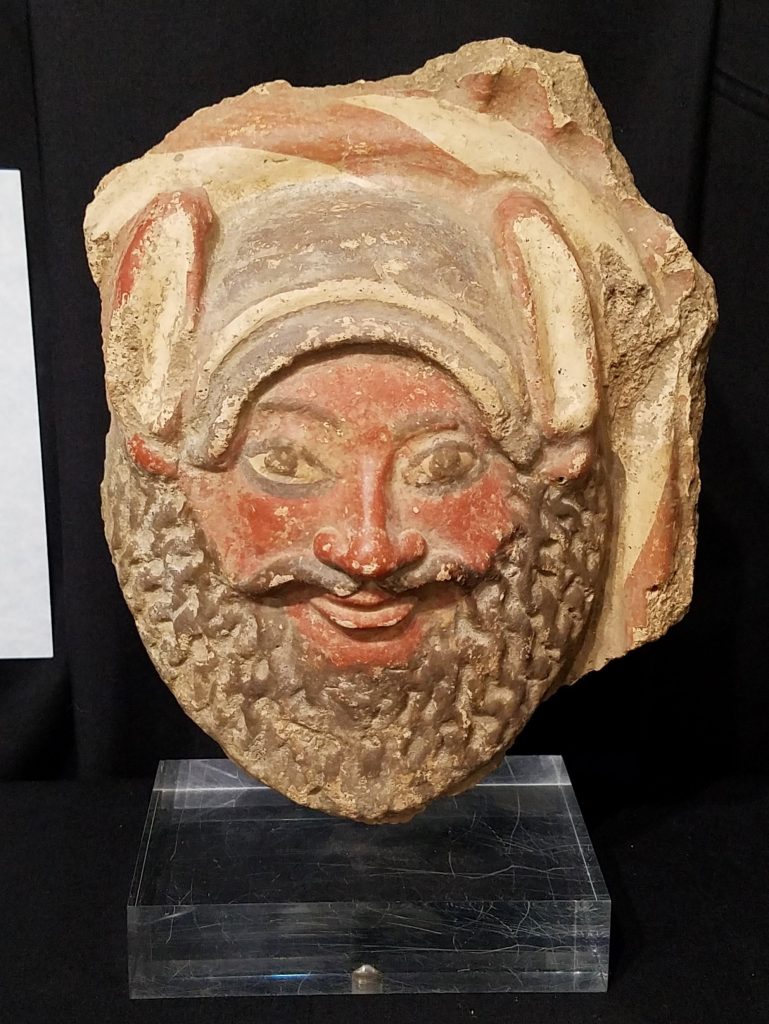

Architecture Figure

650-450 BCE | Archaic Greek (Greece)

1989.03.E.103

This small image of a satyr – a mythical human-like creature – likely originated as part of a roof tile. Artists often depicted satyrs in the company of the god Dionysus, where they emphasized his negative traits of impulsivity, laziness, and lust. The large ears are styled after a horse or goat to emphasize the satyr’s animal-like qualities. The careful craftsmanship exemplifies the expanding Greek artistic tradition begun by the Minoans and perfected by the classical Athenians.

Curated by Leo Ruess

Cart Panel

ca. 1950 CE | Odia (India)

2000.07.E.1

This wooden panel featuring the Hindu deity Kamadhenu adorned one of the carts in the Ratha Yatra festival in Odisha, India. Kamadhenu appears as a reflection of the attendees desire for perfection. The panel represents a renewal of the relationship between Kamadhenu and broader Hindu society. The chosen medium, wood, has been replaced every twelve years for centuries. This represents the renewal of bonds between the deity and his worshippers.

Curated by Ethan Beasley

Mummy Casing

1600-600 BCE | New Kingdom or Late Intermediate (Egypt)

1989.03.E.111

This section of mummy casing consists of paint, plaster, and straw cloth that were used to contain an Egyptian mummy. The painting portrays a number of elaborately decorated Egyptian gods: Re, the falcon-headed sun god; Anubis, the jackal-headed god of mummification; Heket, the frog-headed god of fertility; and Isis, the mother of every pharaoh. Such beautiful painting on a mummy’s casing functioned to elevate the deceased’s life in the afterworld.

Curated by Stephan Pan

Grave Figurines

1570-1069 BCE| New Kingdom (Egypt)

1986.04.E.173-174

Ushabtis are one of the most common artifacts from ancient Egyptian. They first appeared as rough wooden figures in the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030-1650 BCE). By the New Kingdom, they had become more elegant and numerous. The Egyptians believed that they performed tasks for the deceased. The ushabti on the right is in faience – the oldest known glazed ceramic. The ushabti on the left depicts the goddess Isis with her son, Horus, a classic symbol of rebirth.

Curated by Meaghan Bohny

This exhibit was on display from November 21, 2019 to March 16, 2020.