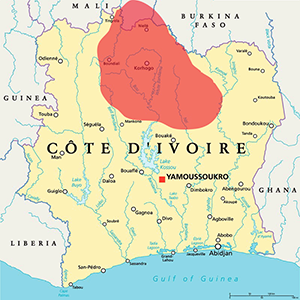

Central Ivory Coast

Baule

The Baule people, who live in central Ivory Coast, share common artistic traditions, as well as political institutions, economic relationships, and religious practices. Anthropologists have documented how these features overlap and influence each other, so that art represents many aspects of Baule life. Baule society is organized around lineage-based kinship systems, where family ties extend beyond immediate relatives to encompass community and regional networks. Kinship and family shape social roles, inheritance patterns, and economic practices—including who becomes an artist. Economically, Baule people traditionally engage in agriculture supplemented by hunting and gathering activities. A subsistence economy underscores the interdependence between humans and the natural world. Religious beliefs among Baule people center on a pantheon of deities and ancestral worship, with divination playing a pivotal role in maintaining spiritual equilibrium and harmony with the environment.

Sauce Pot

#1998.04.E.14 ● Curated by Rebekah Lassiter

This ceramic bowl embodies the basic functionality and form of many utilitarian objects used by Baule people. Based on the form, it is a storage container used for small, but valuable, things. But what would be seen inside the bowl? Similar objects are used to hold medicine, coins, beer, and even water; however, Beverlye Hancock recorded that this one was used to hold spices and sauces, known as tali. Without this first-hand information, it would be impossible to know what the pot was intended to hold.

Sauce Pot

#1998.04.E.17 ● Curated by Gabby Valencia

Kedjenou is a spicy stew of meat and vegetables served over rice or pounded cassava. Taste is the most important concern in cooking, but the visual aspect of preparation is important, too. When Beveryle Hancock tried to purchase this sauce pot she found that the Baule women in charge of making and marketing pottery refused to sell pots that were not up to their high standards. The chip in the rim would prevent its sale normally, but they made an exception for a foreign collector.

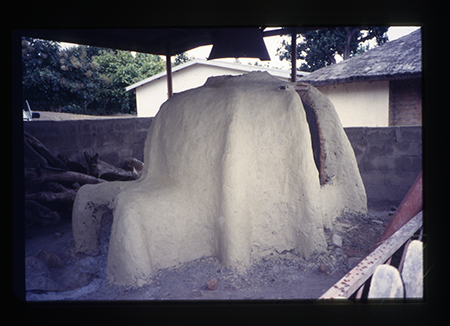

Ivory Coast potters make and decorate pieces from tan clay. After forming, a pit is dug and lined filled with fuel. The pots are burned in the pit, making them hard and changing their color to have a reddish tint. Potters then dip the hot vessels into a mixture of boiled acacia tree pods, which darkens the clay to its final, finished color.

Textile

#1998.04.E.06 ● Curated by Caroline Suber

Baule craftsmen set themselves apart by the quality of their products rather than by innovation in design. How it feels is more important than how it is seen. Seeing can also be deceptive. Just as the cloth is composed of different strips of cotton fabric, woven together with cotton thread, different cultures and practices are “woven into” this quintessentially Baule textile. The ikat dyeing technique and the textile’s red hem can be traced back to influences from the Dyula people.

Fly Whisk

#1998.04.E.22 ● Curated by Abby Costello

Find the fly whisk with the gold-covered handle by looking through this doorway into the next exhibit. The fly whisk is a ceremonial prestige object, typically carried by a Baule chief or presented at his or her funeral. It is meant to be seen during large, public events when the chief is expected to speak to a crowd. Notice how the gold-covered handle easily catches the eye from far away. The dancing motion from its horsehair tail would also draw attention and, like gold, it demonstrates the wealth of the ruler as local pests make it expensive and difficult to keep horses.

Fly whisks handles are carved from wood, allowing the artists to choose from a huge range of shapes and forms. Each client will want something unique, so multiple styles are shown before the final decision. Once selected, the last step is to wrap the wooden handle in precious gold.

Unfinished Sculpture

#1998.04.E.19 ● Curated by Alyssa Eaton

When Beverlye Hancock visited the Baule village of Ouassoukro, she purchased many sculptures from expert carver Kwame Kouakou. The artist was confused when Hancock wanted to buy an unfinished piece from him. According to Hancock, “…he did not like ‘inferior work’ to be bought.” The piece was supposed to be used as reference and practice, not as a display piece on view. Kouakou also believed it had much less importance than the finished sculptures. However, Hancock still purchased the unfinished wood sculpture as she found it fascinating to see the entire process, from wood block to complete figure.

Spirit Spouse

#1998.04.E.23 ● Curated by Carolina González Gutiérrez

Wooden carvings like this one come from the Baule people and serve as spiritual helpers and partners. Artists carve the figures with pleasing appearances meant to appease spirits and bring blessings into the home. This figure’s western clothing symbolizes wealth and prosperity. This style change originated in the 1950s when figures like this began to be seen more frequently in the urban areas that grew during European colonization.

Spirit Spouse

#1998.04.E.20 ● Curated by Steven Sun

This sculpture of a man holding his mustache represents a spirit husband in the Baule culture. Such a sculpture might be used by a diviner whose client thought her real-life husband had interfered with a spirit husband in a parallel world. This friction can cause harm if neglected, so the sculpture becomes a medium to interact with the unseen spirit world. Artist Kwame Kouakou nearly finished this sculpture, but it would have been painted before being used.

Spirit Spouse

#1998.04.E.21 ● Curated by Leah Zhao

A Baule man could be “married” to a female spirit spouse and receive spiritual guidance from her. The curves of her hands holding her breasts symbolize her life-giving powers and ability to fulfill wishes for protection and fertility. She bears rows of keloid scarifications, which are beautiful in the eyes of Baule. Though scarification was viewed negatively by European colonizers, it has remained part of many cultural traditions throughout West Africa.

Unfinished Beads

#1998.04.E.09 ● Curated by Lucy Keenan

A glistening tree of unfinished brass beads, this object showcases the beauty of the lost-wax casting process used by Baule artists. In this process, the final form is first created in wax and coated with clay to form a mold. Molten metal is poured in which melts and displaces the wax. After cooling, the mold is broken, and the cast metal is cleaned. These beads were never cleaned and remain in an unfinished state. Though unintentional, the hardened black clay that maintained the beads’ shape has become a jewel within the interlaced spherical cages—its own form of art.

Passport Masks

#1998.04.E.12.a-b ● Curated by Eloise He

These masks are much smaller than the traditional Baule masks used to cover people’s faces. Rather than being seen during a performance, these miniature masks are seen as a kind of “passport.” Travelers identify themselves by displaying these masks, demonstrating their connections to distant family and friends. Actual performance masks are carved from wood, while these “passport” masks are made by the lost-wax casting process.

Each of these brown pods is a clay mold containing a miniature wax mask. The mold is heated to melt the wax, and a large furnace is used to create a molten copper alloy to refill the molds. Though they could be considered works of art, both the wax sculpture and clay mold are destroyed in the lost wax process, leaving behind the metal mask to be cleaned and polished.

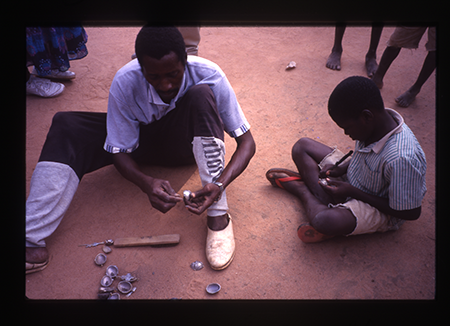

Toy Car

#1998.04.E.01.a ● Curated by Julia Lauterbach

This toy was created by a young boy out of wood, recycled flip flops, wire, and a few nails. He sold his creations to American tourists as they visited artists’ workshops in the Baule community of Ouassou. Though he showed a lot of skill and resourcefulness, he was not yet a professional artist. Is his work fit to be seen alongside traditional arts? Does only the final form matter when determining what is meant to be viewed as art, or are details about the artist also important?

The same artistry and skill that goes into traditional art can go into almost anything. In fact, the boy who made this car was learning to become an artist. He used time between other work to make this car to amuse himself and his friends—not realizing it would be seen as something interesting to tourists!

Explore the other sections of this exhibit