Indigenous Moravians

Yup’ik, Alaska, United States

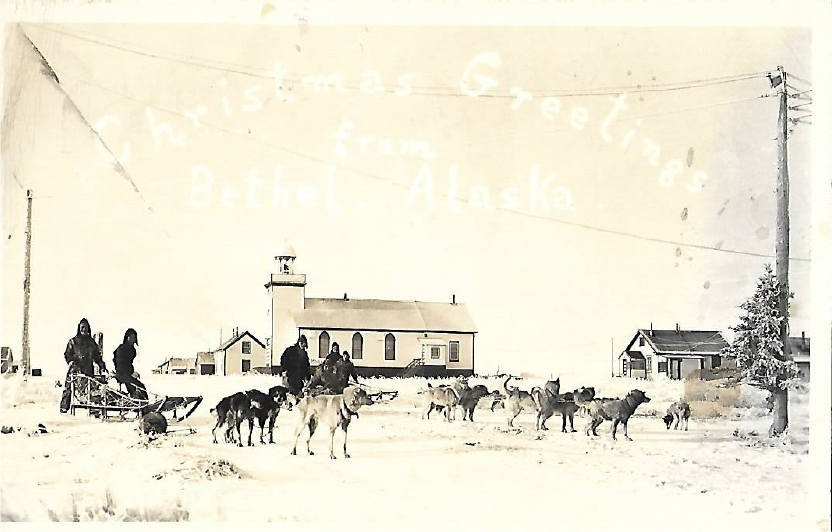

Missionaries found success in many areas of the world. This was, in part, due to an emphasis on teaching the Bible and Christian worship in indigenous languages. In southwestern Alaska, the missionaries John and Edith Kilbuck grew a large congregation by bringing together Moravian ideas with the Yup’ik language and culture. Yup’ik communities were transformed through the Kilbucks’ work into indigenous Moravians — culturally distinct, yet part of the Unitas Fratrum.

John Kilbuck was successful because he knew what it meant to be an indigenous Moravian. Kilbuck was a descendant of Chief Gelelemend, one of the first leaders of the Lenape tribe to join the Moravian Church. His childhood in Kansas among other indigenous people instilled a respect of traditional culture. He volunteered to serve as a missionary and arrived in Alaska in 1885.

Kilbuck and his family lived in Alaska for nearly four decades. During that time, they learned from their Yup’ik neighbors about the intricate tools and technologies needed to survive in the arctic. At the same time, they changed Yup’ik life by encouraging settlement in Bethel, the town they founded, and they translated Church texts into the Yup’ik language to spread the Gospel. The objects that the Kilbucks collected demonstrate this blending of tradition and change in the creation of indigenous Moravian communities.

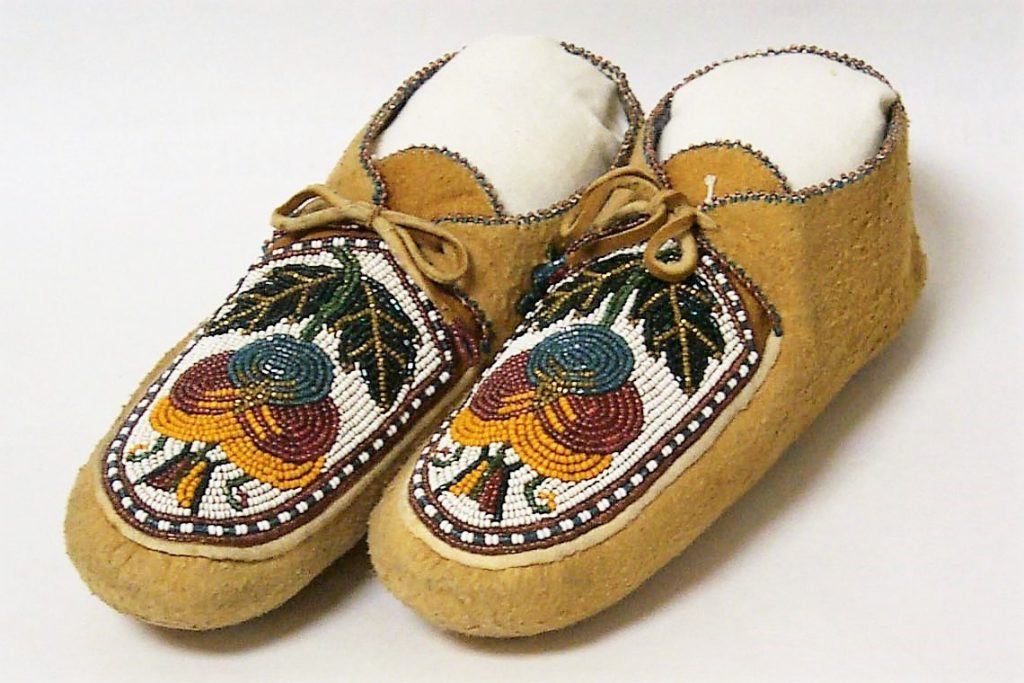

Moccasins (1984.E.0654)

These Yup’ik-made moccasins look like traditional indigenous shoes. But looks can be deceiving! While the shoes are made of local moose hide and use Yup’ik sewing techniques, there is no historical traditional of beaded moccasins in southwest Alaska. A short, soft shoe would be impractical in the deep winter snow or swampy summer mud that blanket the region. The beaded moccasin design was likely introduced by John Kilbuck based on those from his own Lenape tribe.

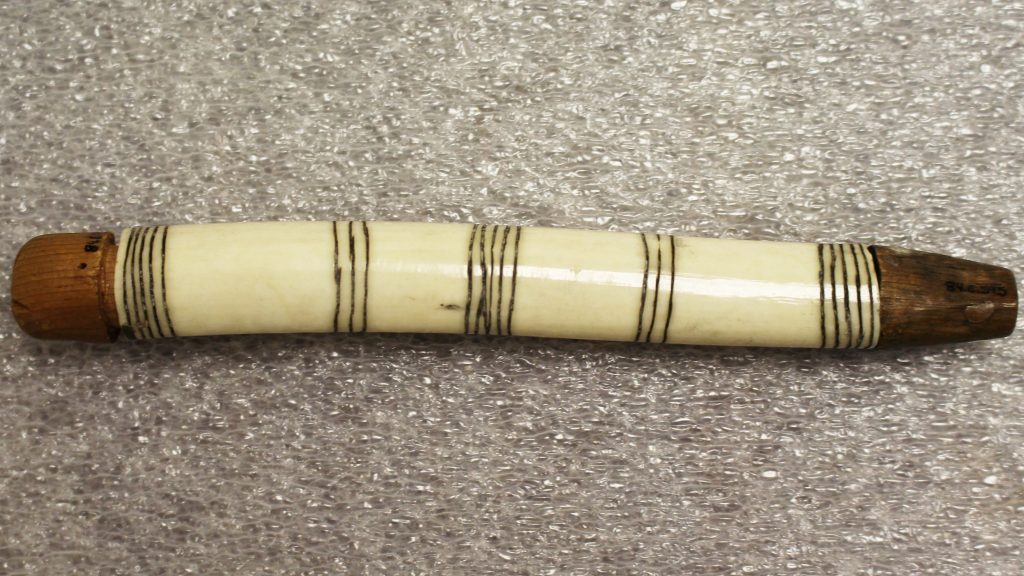

Needles (1984.E.0461.a-d)

Case (1984.E.0595)

Thimble (1984.E.0681)

The Kilbucks were amazed at the resourcefulness of the Yup’ik people. In particular, they thought highly of sewing, weaving, and carving. Marine ivory, derived from whales and walruses, was very rare in the United States but vitally important to Yup’ik communities. The Kilbucks encouraged the Yup’ik to continue using traditional tools even though iron and other materials were available through trade.

Toy (1984.E.0660)

This small bird toy is modeled after a ptarmigan, a kind of grouse native to the artic. The toy is made using traditional Yup’ik weaving techniques and materials. The local subject matter and indigenous methods suggest that this object is thoroughly Yup’ik. Animal models, however, were not common toys. Instead, this concept was introduced by the Kilbucks as a means of encouraging handicraft skills among the young pupils at their missionary school.

Spoon and Fork (1984.E.1194 & 1984.E.1195)

The luminescent yellow sheen of these implements is a telling sign they are carved from whale ivory. This distinctly Yup’ik material is challenged, however, by the unusual form. The oversized spoon and fork make a “salad set” used for serving guests during an elaborate meal. This kind of meal presentation, as well as the availability of salads, is much more Euro-American than it is Yup’ik.

Explore the other sections of the exhibit below