Animal Origin: Tokens and Tools from Faunal Remains

Since we first arose, humankind has created materials out of animal remains. This exhibit explores objects created for a variety of different uses from cultures throughout the globe. Some of the objects are outdated and some still very much in use. What unites them is that they all incorporate animal parts in their construction. What is the connection between the object’s function and the animal used? Why are some considered ceremonial while others simply tools? Are there similarities between objects created across the world from each other? This exhibit reveals the purposes of these objects, both obvious and obscure. Feather and fur, tooth and nail, the objects on display show the many ways that people have looked at an animal and found a creative use for them.

Shield

Early 20th century, Kenya

Hide, wood, twine, shell, pigments

The shield’s maker used wood for the frame and handle, and cow leather for the outer covering. The materials were not particularly valuable, but the intricate designs were meaningful. Each shield displayed the prestige of the person wielding it within their lineage, a family network that collectively owned vast herds of cattle. Once important protection for hunters and warriors, contemporary Maasai no longer use these shields.

Mask

Late 20th century, Guinea Bissau

Wood, horn, glass, yarn, twine, pigments

The Dugn’be buffalo mask is part of a contemporary masquerade tradition in Bidjogo communities. Many artificial materials are used in its construction, though the horns are real to emphasize the animal’s power. There are many different buffalo masks within this society representing different “coming of age” periods. The Dugn’be masks are used exclusively in the initiation rituals of young men into adulthood. With this mask, they perform a wild dance that evokes a buffalo, representing the initiate’s lack of control and need to be tamed.

Knife

Late 19th century, United States (Alaska)

Ivory (marine)

This ivory knife was used by Yup’ik children, primarily little girls, to draw stories in the snow. Players might depict objects in a game similar to Pictionary. These knives are not sharp and were only used for entertainment. Yup’ik children still play storytelling games; however knives made from walrus or sperm whale ivory have been replaced by mass consumer goods like plastic butter knives.

Bottle

Mid-20th century, Botswana

Eggshell

Ostrich eggs have traditionally been used as canteens by the San people while traveling or foraging. Ostrich eggs are also very nutritious, equivalent to about two dozen chicken eggs. Acquiring an egg is not easy because ostriches can slash with their long talons. Successful hunters will locate an ostrich nest and either wait for the vigilant adults to leave or use a high risk strategy of scaring it away.

Cups

Mid-20th century, Nigeria

Horn

These cupping horns were used in medical treatments that bring blood to the surface of the skin via suction. Practitioners make a small incision on their achy body part, then light a small fire in the animal horn and place it over the wound. The dying fire creates a vacuum that draws blood to the skin. Practitioners give many explanations to why this is helpful despite no evidence of a specific medical benefit. The use of these has increased in recent times. In the United States, some kinds of cupping have become popular with athletes, such as Olympic swimmer Michael Phelps.

Robe

Late 19th century, United States

Hide, pigments

This deerskin robe was worn by a female child for a curing ceremony. The Comanche believed that the deer and buffalo which provided hides were part of a spiritual network that included humans. Wearing hides let people take on the animals’ valued qualities, like toughness. The central hourglass-like shape surrounded by the colorful border is an indication of the robe’s ceremonial purpose.

Sculpture

Early 20th century, China

Ivory (elephant), wood

This particular elephant tusk depicts carved lions, elephants, and a small building. Chinese ivory carving was an art form as well as a booming business for centuries. The art form demands great skill, and only about ten percent of apprentices would became professional carvers. Asian and African elephants became critically endangered during the 20th century because of the ivory trade. In 2017, China officially banned all commercial processing and sale of elephant tusks. However, market demand for ivory continues to threaten herds.

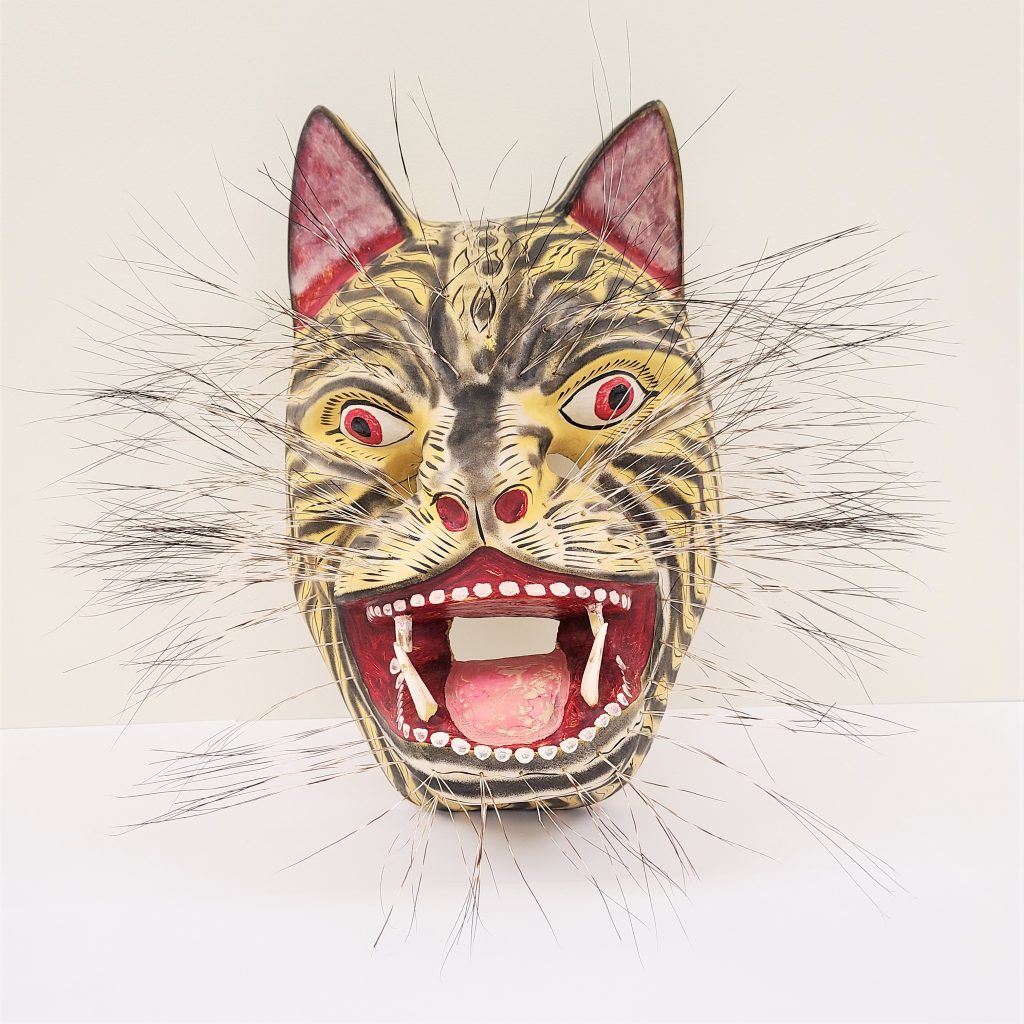

Mask

Late 20th century, Mexico

Wood, hair, teeth, pigments

This colorful tiger mask is part of a traditional costume used in the “the dance of the tiger” throughout southern Mexico. The dance likely originated in the Aztec Empire or earlier, though the name “tiger” is a recent invention. Earlier masks were likely modeled after jaguars, the large cat native to Mexico. During the dance, the tiger attacks farmers’ crops and attempts to destroy them until the entire community chases it away. This tiger mask doesn’t actually contain any materials from a cat: the teeth and whiskers are from a wild boar.

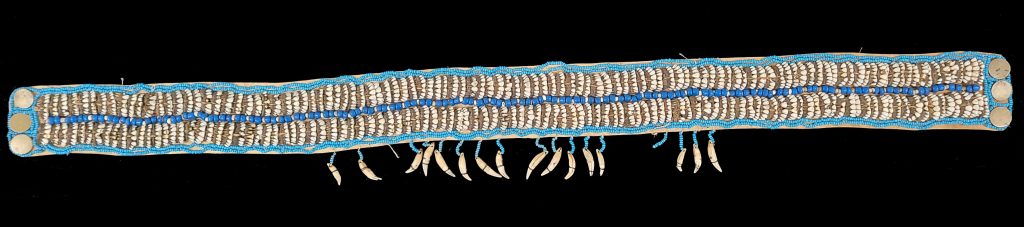

Belt

Late 19th century, United States (Alaska)

Hide, teeth, glass, copper, string

This caribou hide belt is adorned with beads, buttons, and two rows of caribou teeth as well as fox teeth. In total, there are 221 sets of caribou incisors and 23 fox teeth. It is likely that single Yup’ik hunter killed these animals. While men were, and continue to be, the primary hunters in Yup’ik society, it was women that wore these belts. If the belt had passed through enough generations, it acquired healing powers that were accessed by striking the afflicted area.

Model

Late 19th century, Canada

Hide, wood, ivory (marine), hair, string

This model is made of wood and sealskin in the same fashion as a life-sized Inuit kayak. The Inuit used kayaks for hunting seals and other aquatic arctic mammals. These replicas were made for Moravian missionaries who established trading posts beginning in the 18th century. Moravian missionaries would trade European goods for these souvenirs and send them to their friends and families. Kayaking became popular in Europe in the 19th century and became an Olympic sport in 1936.

Knife

Late 20th century, Papua New Guinea

Bone

For many cultures in Papua New Guinea, daggers carved from a femur bone were both close combat weapons and status symbols among men. Warriors who carried these daggers possessed exemplary fighting skills. This dagger is made from the bone of a large, flightless bird called a cassowary. Cassowaries are the deadliest birds in the world, capable of killing humans with clawed kicks. Some daggers were made from human femurs, carrying the highest social status. Though no longer used in combat, cassowary bone daggers are still used ceremonially.

Sword

Late 19th century, Sudan

Hide, steel, wood, ivory (elephant), bone, teeth, string

This sword and scabbard was likely created in Sudan, indicated by the shape of its pommel. It was used for personal protection, but its most unique characteristic is its scabbard. It is made from an entire small crocodile, still present with bones and teeth. Crocodiles were used symbolically during the Mahdist Revolution in Sudan during the 1880s. Crocodiles used as equivalents for dragons, a symbol of power in Islamic Sufi tradition. Many weapons were taken out of Sudan as war souvenirs after the British re-colonized Sudan in 1898.

Hat

Early 20th century, Democratic Republic of the Congo

Feathers, palm fiber

Dozens of hat styles were in vogue within the Kuba kingdom’s traditional court. This hat woven with iridescent bird feathers was considered to be a flashy, young person’s style. The hat’s maker has creatively emphasized the feathers’ sharp angles to make a visual statement. Though colorful and eye-catching, the hat doesn’t signify social prestige or military rank as some other hats do. Older and wealthier courtier would likely opt for a more conservative hat.

What about Endangered Species?

The objects in this exhibit show the diverse ways that human societies have exploited animals as natural resources. Many of these objects are decades old and were produced in societies with plentiful animals and a healthy ecosystem. Unfortunately, many could not be made today as the animals they originate from are threatened or endangered. Habitat loss, climate change, and pollution have all contributed to vanishing wildlife population, but over-harvesting—especially for export—is also a concern.

In the early 1960s, international discussion began focusing on the rate at which the world’s wild animals and plants were being threatened by unregulated international trade. The solution came in the form of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), an international treaty that regulates and prohibits the trade of protected species. The objects on display containing elephant ivory or tropical bird feathers are legal because they were created before 1970 when CITES went into effect. Many countries enact additional laws to protect wildlife from humans, such as the US law that prohibits harvesting marine ivory from whales and walruses, but carves out an exemption for Alaskan Native communities.

This exhibit was curated by WFU intern Robby Outland (’21). It was on exhibit from March 1, 2021 to April 14, 2022.