All the King’s Men: Status and Power in Africa

In African societies, social and political power is often visually expressed through diverse material culture, reflecting the broad range of kingdoms, federations, chiefdoms, and empires that arose on the continent. Within these contexts, art, clothing, and symbolic artifacts convey the roles and status of men and women. Traditional African art often depicts gender-specific ceremonies, courtly rituals, and political roles. Clothing, jewelry, and beadwork can signify the gender identity of its wearer, as well as gendered political roles like “male heir” or “queen mother.” Sculptures and masks depicting important ancestors and historical events try to naturalize gender roles by placing them in a mythic past.

Visual material culture not only mirrors existing gender roles but also reinforces their transmission across generations. The objects on display in this exhibit are ceremonial and artistic objects that are highly esteemed within their communities. By interacting with these objects through ceremonies or through display, individuals internalize societal expectations about how they should act based on their gender and political role. Objects shape perceptions of masculinity and femininity by connecting gender toideas of prestige, power, value, and beauty.

But, these objects are not static. How and why they are made is shaped by internal and external politics, and these change with the political currents. From the late 19th century to the middle of the 20th century, European colonialism significantly impacted gender roles in Africa, leading to profound social and cultural transformations. European colonial powers imposed their own gender norms, often reinforcing existing patriarchal systems and marginalizing women. Colonial governments reorganized land ownership, but often excluded women, even when they were the traditional landowners. Colonialism also created legal challenges by enacting laws that failed to recognize and protect indigenous women’s rights. Since many collections of African art originate during this time period, museum collections often over-represent this male bias. The objects in this exhibit were curated by students in Dr. Andrew Gurstelle’s Fall 2023 course, “Introduction to Museum Studies,” to investigate how gender is represented in the Lam Museum’s collection.

This exhibit was on display from January 23, 2024 to January 25, 2025.

Explore the objects in this exhibit below

Sculpture

Yoruba, Nigeria

#2017.05.E.0001 ● Written by Caroline Mederos

This figure shows a horseman carrying the reigns of his horse in his left hand and a sword in his right hand. The figure is disproportionately larger than his horse to emphasize the rider’s importance as the owner and controller of the horse. This is consistent with Yoruba art techniques that use scale and proportion to visualize power. The horse represents strength, triumph, and prestige due to its association with military history. Horseman sculptures were displayed in the home of a titled man or in mixed gender religious settings to show a deity’s elevated status over its worshippers.

Vessel

Baule, Ivory Coast

#1998.04.E.18 ● Written by Julia Jiang

This pot is made from fired clay and colored with a tree bark infusion. The various symbols modeled onto the vessel’s shoulder include a snake, chameleon, cowrie shells, and birds. The pot is used for the collection, storage, and serving of palm wine for rituals like births, marriages, and funerals. Both men and women sponsor palm wine drinking to gain social prestige during events.

Skirt

Kuba, Democratic Republic of the Congo

#1992.04.E.03 ● Written by Diana Frelinghuysen

This ceremonial dance skirt is woven from raffia fiber embroidered and dyed to create geometric patterns. Raffia garments are known for their decorations and designs which signified political prestige within the precolonial Kuba Kingdom. Some designs were worn exclusively by noble and high-ranking women. For example, the female relative closest to the king would have worn this ceremonial piece. It was given by the royal family to Dr. James Lankton, who donated it to the Lam Museum.

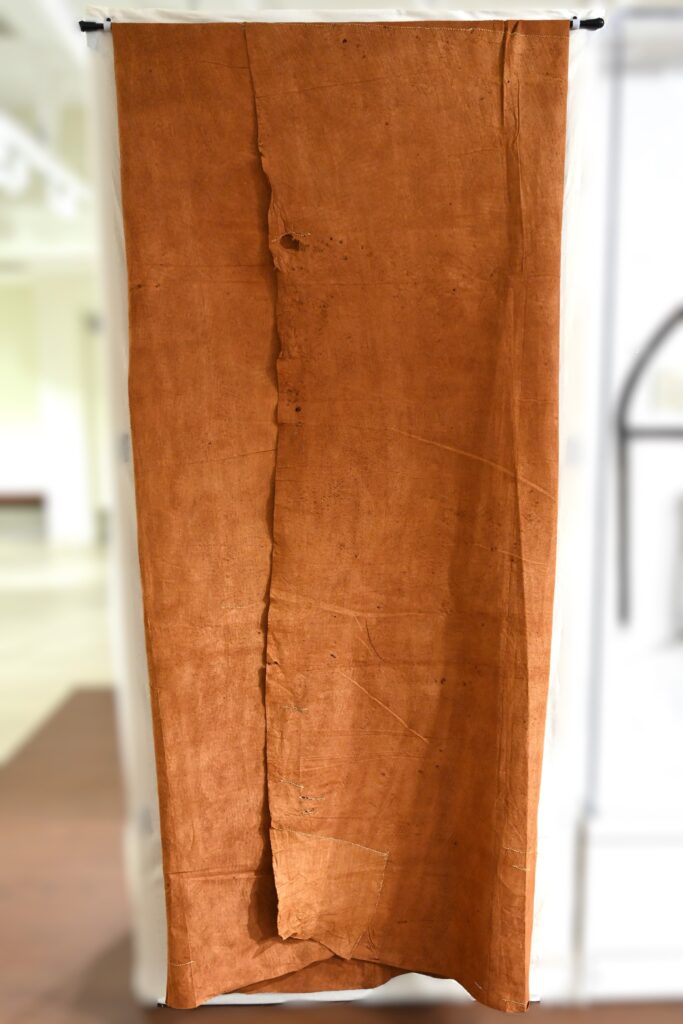

Textile

Baganda, Uganda

#2005.11.E.046 ● Written by Samuel Francis

This large bark cloth tapestry is made from the mutuba (Ficus natalensis) tree. Its creation is a labor-intensive process that involves scraping, soaking, beating, and drying the inner bark. The beating process imparts the desired texture and thickness. The resulting cloth has a rich history and cultural significance as a ceremonial wrapped garment connected to the Buganda Kingdom’s royal court. It was worn by both men and women. Traditionally, bark cloth has been used to make clothing, accessories, furnishings, and even tents. Today, it is recognized by UNESCO as part of the world’s intangible heritage.

Knife

Arab/Mahdist, Sudan

#1986.04.E.080.a-b ● Written by Gentry Conner

This deadly knife and crocodile scabbard are from Sudan, where they were made in the late 19th century. Symbolizing threat and violence, this knife was used by soldiers in Sudan to fight in the Mahdist Revolution against British colonial rule. The use of crocodile comes from Madhist beliefs, as the animal is noted for its great strength. Its presence on this artifact represents the idea of strong military leadership valued during that moment in time.

Knife

Sara, Chad

#1999.08.E.6 ● Written by Leilei Pu

This iron ngalio, also known as a throwing knife, was crafted by a member of the Kodi blacksmith caste. For the Sara, knives served dual purposes for both hunting and combat. The knives can be thrown remarkably far, reaching distances of up to 30 meters. They were commonly carried in sets of three within a leather pouch. The knives themselves can be considered either male or female. The blade projecting out from the middle of this knife’s “body” suggests that it is a male.

Knife

Mangbetu, Democratic Republic of the Congo

#1993.09.E.044 ● Written by Cole Cook

Angled knives were mainly used in two ways: currency in trade and as a show of status. As a trade object, knives were used by everyone as a standardized amount of metal with which to barter. As a status object, a man’s status would be shown through decorations on the knife as well as the materials used to build it. Knives like this one would not have been crafted for war, but displayed to other men as ceremonial pieces and carried under the arm, slung around the shoulder, or sheathed at the hip.

Axe

Songye, Democratic Republic of the Congo

#1986.04.E.054 ● Written by Chloe Edelman

The Songye people have a rich history of subsistence farming, hunting, and fishing, though they are also known for trade. Prior to European colonization, axes were powerful symbols of royal authority that showcased the owner’s mastery over economic production and connections to international trade. The iron also demonstrated technical expertise and secret knowledge. The axes also feature intricate decorations in copper, a precious metal from the Zambezi River that was used as a trade currency throughout the region.

Currency

Kissi, Sierra Leone or Liberia

#1997.06.E.133 ● Written by Anne Jones

This bundle of twisted pieces of metal is kilinde, a common currency used by the Kissi people, which circulated in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia from the 1800s to 1970s. One of the earliest forms of local currency in Sub-Saharan Africa, kilinde could be exchanged for quantities of rice and cassava. The differently shaped ends symbolize wings and fish tails, a visual metaphor for living souls. This comes from the use of kilinde during ceremonies such as burials in which life is exchanged for death.

Club

Zulu, South Africa

#1985.E.062 ● Written by Charlie Knox

With over 75 different names for sticks in the Zulu language, the club has quite a significance in their culture. This wooden club is styled after war club, but it is too small to be practically used for fighting. Instead, it was likely used by young men for dances or as a walking stick. By imitating a weapon of warfare but placing it in a different social context, this object shows the close connection between aggressiveness and masculinity in traditional Zulu gender norms.

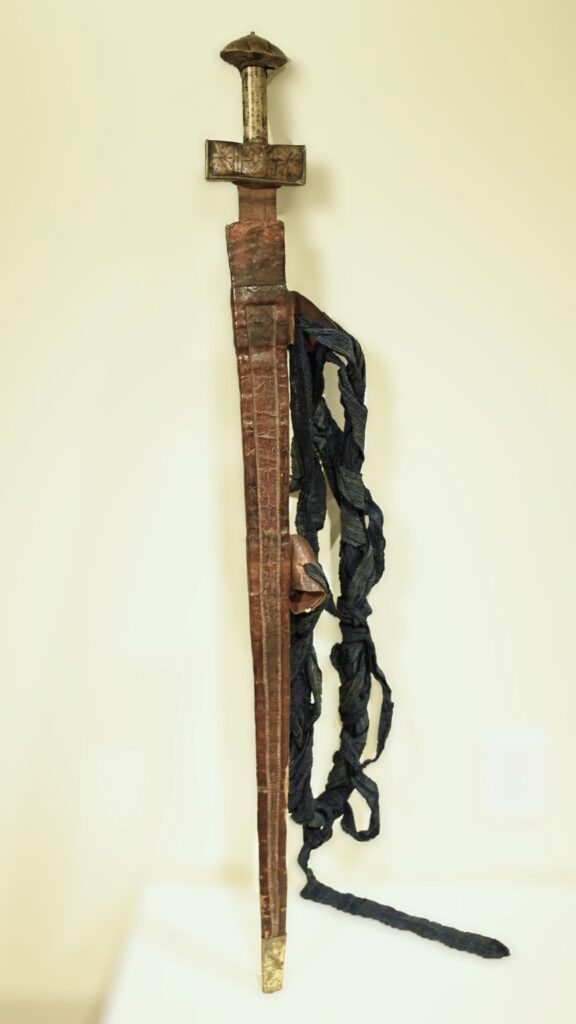

Sword

Tuareg, Nigeria

#2005.07.E.08.a-b ● Written by Annelise Witcher

In the past, only men in the Tuareg warrior class (called the Ihaggaren) were permitted to wear the takouba, or double-edged sword. It is worn slung around the shoulders by indigo-dyed cotton straps attached to the scabbard. Today, the takouba is a symbol of culture, heritage, and courage, usually worn only during celebrations or special occasions. Young Tuareg men are presented with a takouba as a rite of passage into adulthood.

Sculpture

Edo, Nigeria

#2016.01.E.01 ● Written by Keira Yu

This copper-alloy bust depicts Oba Akenzua II the king of Benin, who reigned from 1933 to 1978. Akenzua II is portrayed wearing traditional coral head regalia and a winged crown, symbols that represent his identity as the leader of the kingdom. Traditional portraits similar to this one are used in Edo culture by the king’s descendants to honor his leadership. Many commemorative and ritual objects were stolen by the British during the colonial period. After Nigeria gained independence in 1960, the commemorative practices were rekindled in Benin, along with the use of this type of sculpture.

Footwear

Hausa, Nigeria

#2018.07.E.08.a-b ● Written by Isabel Liceaga

The Hausa, one of Nigeria’s largest ethnic groups, are known for their distinct attire that expresses their social identity. Spats are practical articles used to protect boots while riding horses, but these spats are decorative and meant to convey the wearer’s wealth—it is expensive to own a horse! They feature geometric bead patterns, intertwining blue, white, and black beads with motifs dating back to medieval Islamic traditions. Craftsmanship is evident in every detail, showcasing the talents of Hausa artisans and the status of their patrons. Though horses signified an entire family’s wealth, they were ridden only by elite men during ceremonies or war.

Sword

Ngala, Democratic Republic of the Congo

#1997.06.E.099 ● Written by Walker Previdi & Steven Xu

The Ngala people emphasize a warrior culture that connects toughness and violence to masculinity and nobility. Due to their warrior heritage, this ngulu style execution knife is a great insight into their culture. Prior to European colonization, knives like this one were used in ceremonies of peace between two warring tribes where an execution of a prisoner was conducted to signify a truce. This specific knife was not used for actual executions. After beheadings were banned by the Belgian colonial government, the use of ritual knives evolved to become performance objects in the Likbeti dance ritual.

Vessel

Bamileke, Cameroon

#2001.10.E.33 ● Written by Zoie Irby

Adorned with a spider on its exterior, this ceramic pot references the creation story of the Bamileke people. It tells of a female spider that wove a web and caught all of creation. From her catch, she then birthed the world and gave it life. Because of its size, this particular pot was likely created to hold palm wine. It resembles other wine vessels used by Bamileke royalty.

Fly Whisk

Baule, Ivory Coast

1998.04.E.22

Women in traditional Baule society had equal access to politics as men and could be leaders of their extended kin group, village, or region. In the early 20th century, colonial laws reduced the power of women by excluding them from the government. Women have been able to retain their status through entrepreneurship. This fly whisk is a traditional symbol of authority that reflects both the power and wealth of its bearer. The elephant finial stands in for political power, while the gold leaf covering is a showy display of connections to the local gold trade.

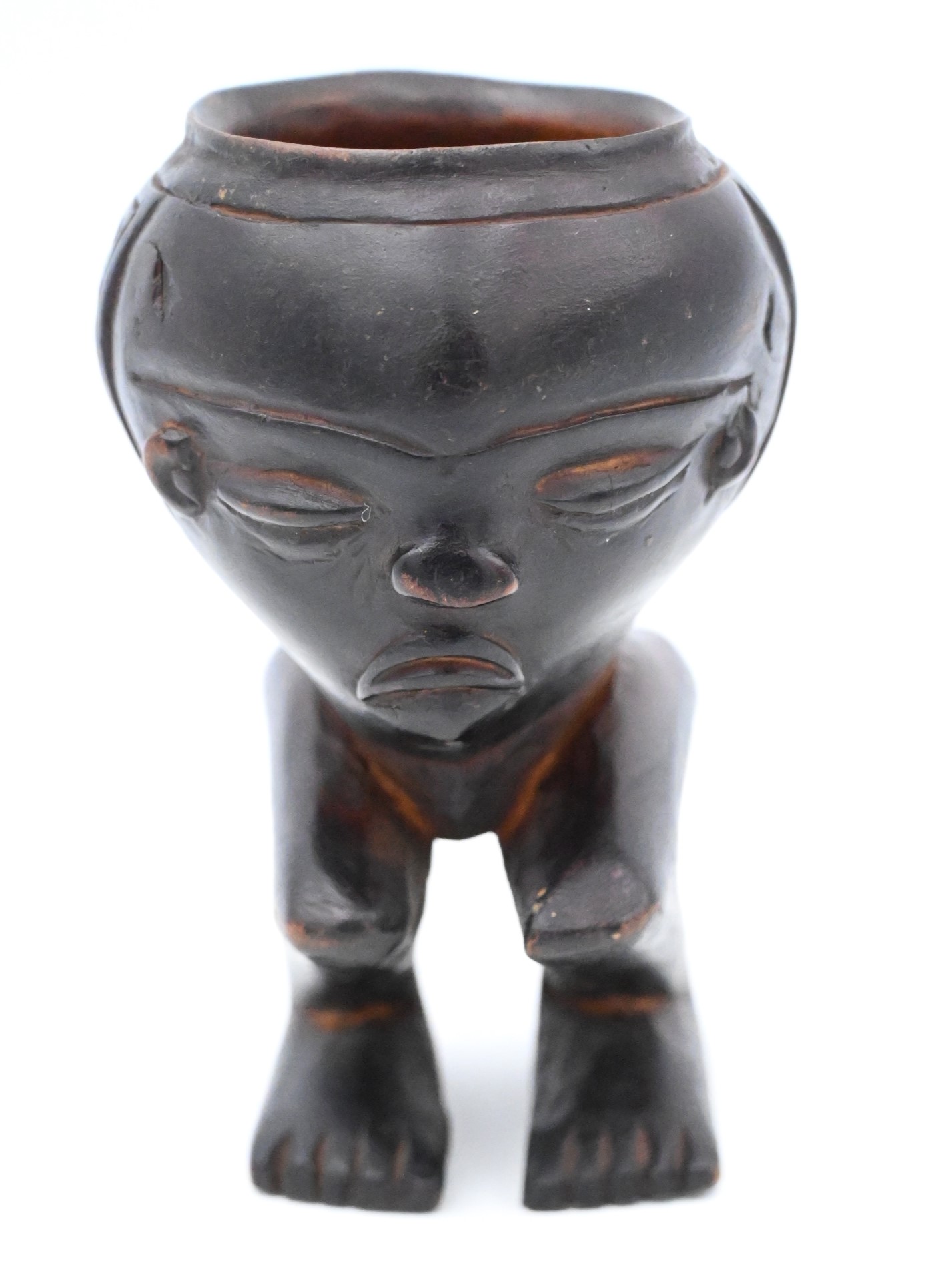

Cup

Pende, Democratic Republic of the Congo

#1997.06.E.125 ● Written by Zoe Panzer

This cup was traditionally used to drink palm wine made from raffia palm tree sap. Some sources claim it was used only in ceremonial or religious contexts by men with titles or seniority, while others cite use in daily social settings, so the value of these cups likely changed through time and between communities. Faces on cups are common, but again the meaning is ambiguous. Some sources say that the faces represent certain moods to emulate or avoid, while other sources say that the figures represent stereotypical characters such as a chief or diviner. Drinking and joking about leaders in the community is an informal way to create political alliances.

Textile

Ewe, Ghana

#1997.06.E.010 ● Written by Helen Player

This kente cloth was made by an Ewe artist in the Asante style. These textiles are traditionally woven only by men and were once reserved only for the Ashanti royalty and their court. After the Ewe people were conquered by the Ashanti kingdom, they incorporated kente into special occasion dress where it has remained a status symbol. Many artists give kente colors symbolic meaning: yellow for preciousness, red for life, green for land and nature, blue for peace, pink for prosperity, and gold for power.

Sculptures

Bamum, Cameroon

#2003.08.E.019.a-b

Brass leopards once adorned the throne room of the king of Benin, now in present-day Nigeria. These royal artifacts, along with thousands of other treasures, were looted by the British army after they invaded the palace in 1897. Many refugees were forced out of the kingdom after the destruction of the capitol and its absorption into the colony of Nigeria. Some royal artists settled in the neighboring colony of Cameroon, where they began to replicate royal arts for a new clientele: tourists!

Throne

Tikar, Cameroon

#2003.08.E.017

Singing and dancing people are the literal base of support for the ruler in this dioramic throne. Thrones are always potent political symbols, but this work goes even further by portraying the chief as central to his constituents, who are more than happy to prop him up. Musicians and attendants flank his figure, which would mirror the real-life court of a Tikar leader. The two women who make up the arms of the throne may be the chief’s wives based on their hairstyles, which signify a wealthy bride.

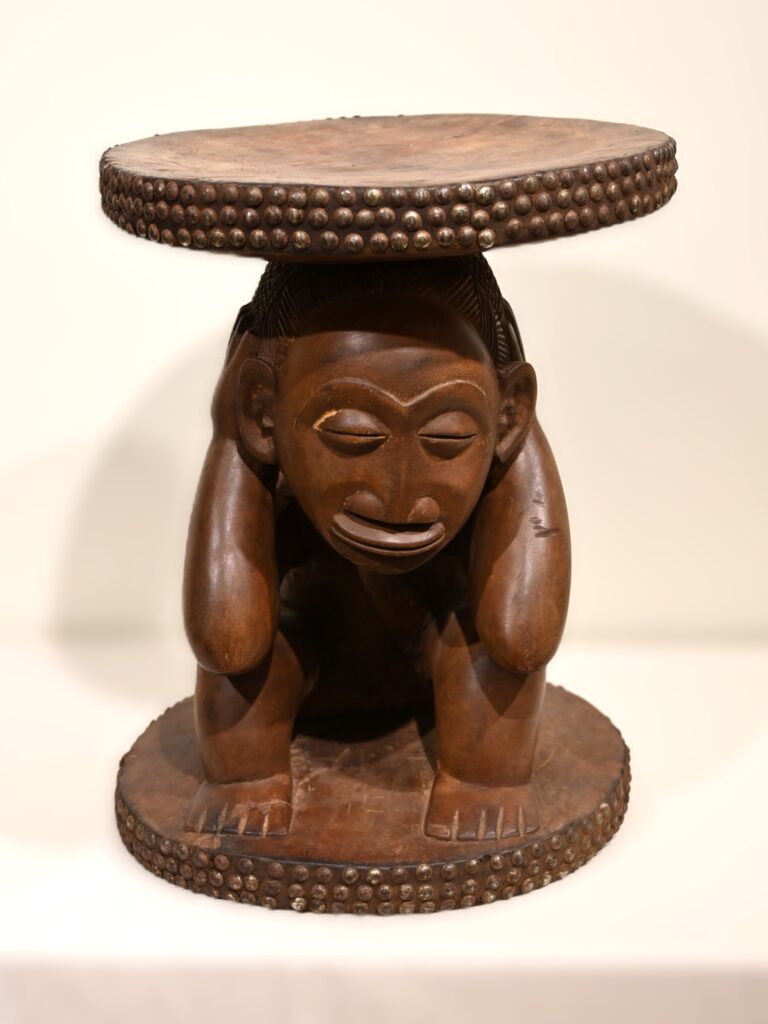

Stool

Luba, Democratic Republic of the Congo

#2003.04.E.4 ● Written by Kevin Chuang

Stools are literal seats of power, used by political dignitaries to show the prestige of their office. The carvings on Luba stools hold deep cultural significance and typically symbolize ancestors, leaders, and spirits. Though stools were owned and displayed primarily by men, their symbolism usually testifies to the spiritual power of women. The female figure in this stool sits on one disc, while supporting another—a visual metaphor for bridging the gap between the earthly and the divine.

Mask

Kuba, Democratic Republic of the Congo

#1997.06.E.090 ● Written by Jamie Wu

This helmet mask symbolizes the elephant by mimicking its iconic trunk to show supremacy and wealth. It is made from many different materials such as beads, fabric, wood, cowrie shells, raffia, silk, and monkey hair. The collective display of rare and valuable materials in geometric sequence illustrates the power of the Kuba king. This mukenga-style mask is one of three in a series of masks representing the kingdom’s founding mythology.

Flags

Fante, Ghana

#2023.12.E.16, 18, 19

The dynamic imagery of these frankaa, or battle flags, match the lively contexts in which they would be paraded and danced about. Every Fante community has its own asafo companies that act as local militia and men’s secret society. The asafo rose to prominence by allying with European powers—and borrowed their convention of using flags during military parades. Each flag features a smaller flag as its canton, which signifies which country was the dominant political power during the company’s founding: the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, or the modern nation of Ghana.